"Opus operatum" translates as "the work wrought." I like that word: wrought. I haven't generally feel like my poetry is, for the most part, something that IS wrought; but I've always liked the idea. It makes me think of my grandfather's hands, the hands of a carpenter, and the way he always smelled of wood shavings and nicotine. Wrought like I imagined the way cars, trains, and airplanes were made; wrought like the real swords I pretended stick were in endless, imaginative games. Wrought, something beaten our or shaped by hammering. It's one of the crunchy words that gets used to describe masculinized creation. Nations are wrought. Industries are wrought and do themselves take credit for what people's hands make. When poets speak of poetry being wrought, it's mostly in a masculine sense; and as I mention, I like the word because it's chewy and because of the idylls it creates when I turn it around in my mind.

But poetry for me isn't wrought. Not wrought, not wrangled, not forced, not carved, not fought for. It's not drip and dribble inspiration from the muses. It's also not something birthed; not because I think a poet necessarily needs a uterus to birth a poem, but because that's not ever been my experience with language. And when I read poets speaking of their work... and sometimes worse, when I read people writing about someone else's poetry... the verbiage is generally an active one. It's like we have to somehow justify the truth that writers spend a significant amount of time sitting down, or maybe trying to contradict the trope of the physically ineffectual wordsmith, or maybe it's an attempt to articulate the sensation of writing to a reader who maybe hasn't had the experience.

The problem with metaphors about writing is that eventually all metaphors break down. Even (and especially) the good ones. After so undetermined and trope specific amount of time time has passed, even the best metaphors need their context explained in order to truly make sense. The same is true of movies, and of a large amount of music. This break down explains why "To thine own self be true" is almost always treated as a self-affirming mantra and why Romeo and Juliet is still seen as a soppy love story. And if ol' Billy Shakespeare isn't immune, NOTHING is.

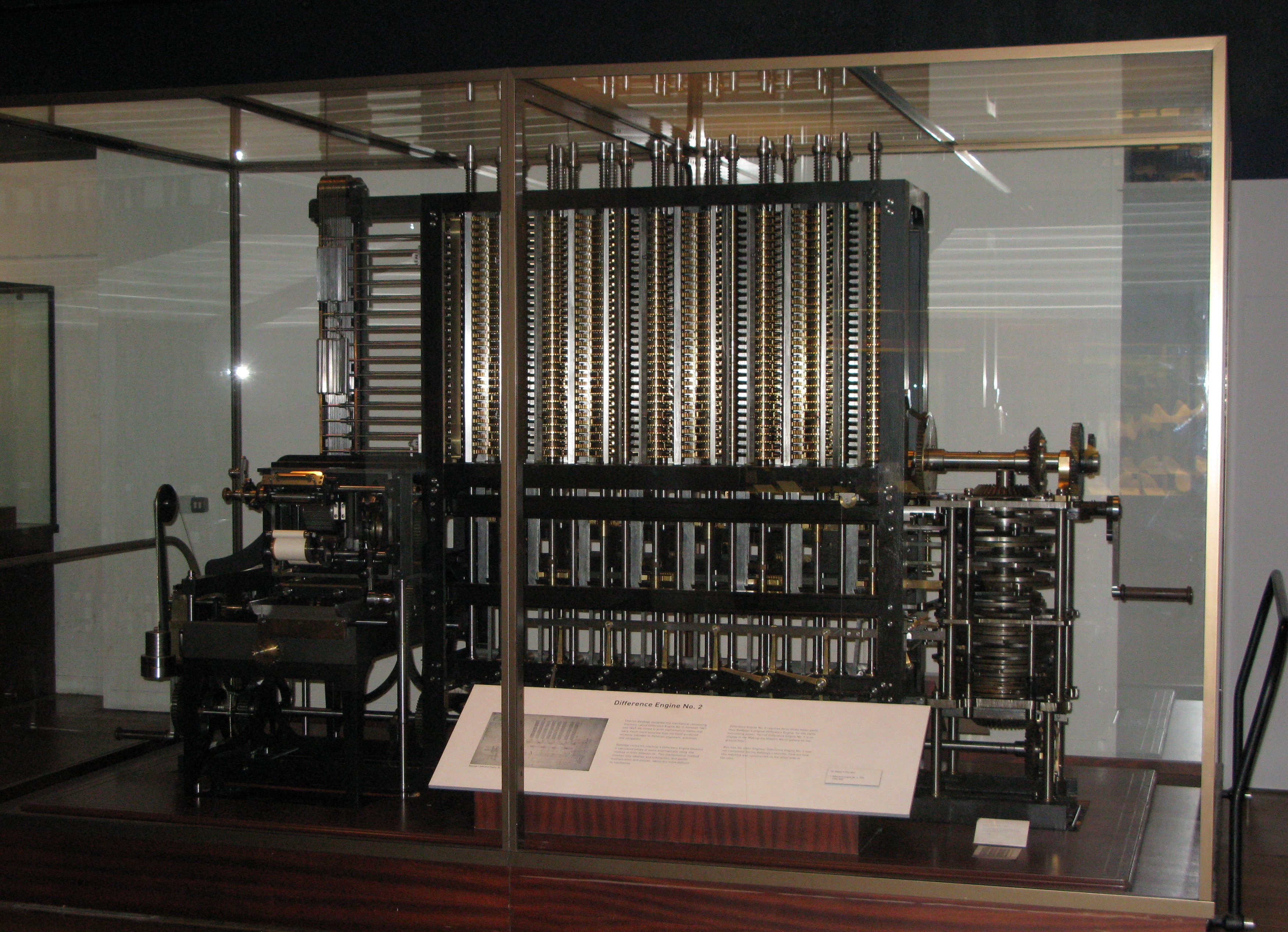

The Difference Engine -- what amounts to the first ever computer, was created by Charles Babbage in 18. And although now it's just a calculator that's far too big to fit in your hip pocket to help figure out the percentage amount of a tip, this it's one of those inventions that has transformed the world we live in. And most people -- many of us who use computers daily whether we like them or not -- don't even know his name.

I bring this up because outside of a certain context, Babbage's mechanical brain is easy to dismiss. So to is the fact that automatons (read: robots) are recorded as having existed long before the 18th Century, when they were popularized in Europe... some accounts even written about in ancient China (400 BCE).

There are people for whom poetry is just another difference engine, or, like Jacques de Vaucanson's Flute Player (1737) is nothing but a curiosity. I find most people who don't like poetry either weren't introduced to it with the appropriate context or dismiss it because it's not generally something someone does "for a living." Making money as a poet usually means doing any number of things, and in a culture driven by neoliberal capitalism, what a person earns ends up being more important than what a person does, what they make, or what they create.

I think of myself not as someone who wroughts language into poetry but as a lens. The world passes through me like light through a lens and what poetry comes of is nothing but refracted lights and images. This metaphor, too, is breaking down -- like Babbage's machine, the legendary Yen Shi's artificial man, or King Solomon's throne (in some writings described as an ivory and gold mechanical wonder.)